From the postcard-perfect Coral Bay to the hidden beauty of Secret Cove, these spots promise stunning photos and unforgettable views.

GVI

Posted: August 29, 2024

Lindsey Chynoweth

Posted: January 2, 2019

Original photo: Chris Hoare

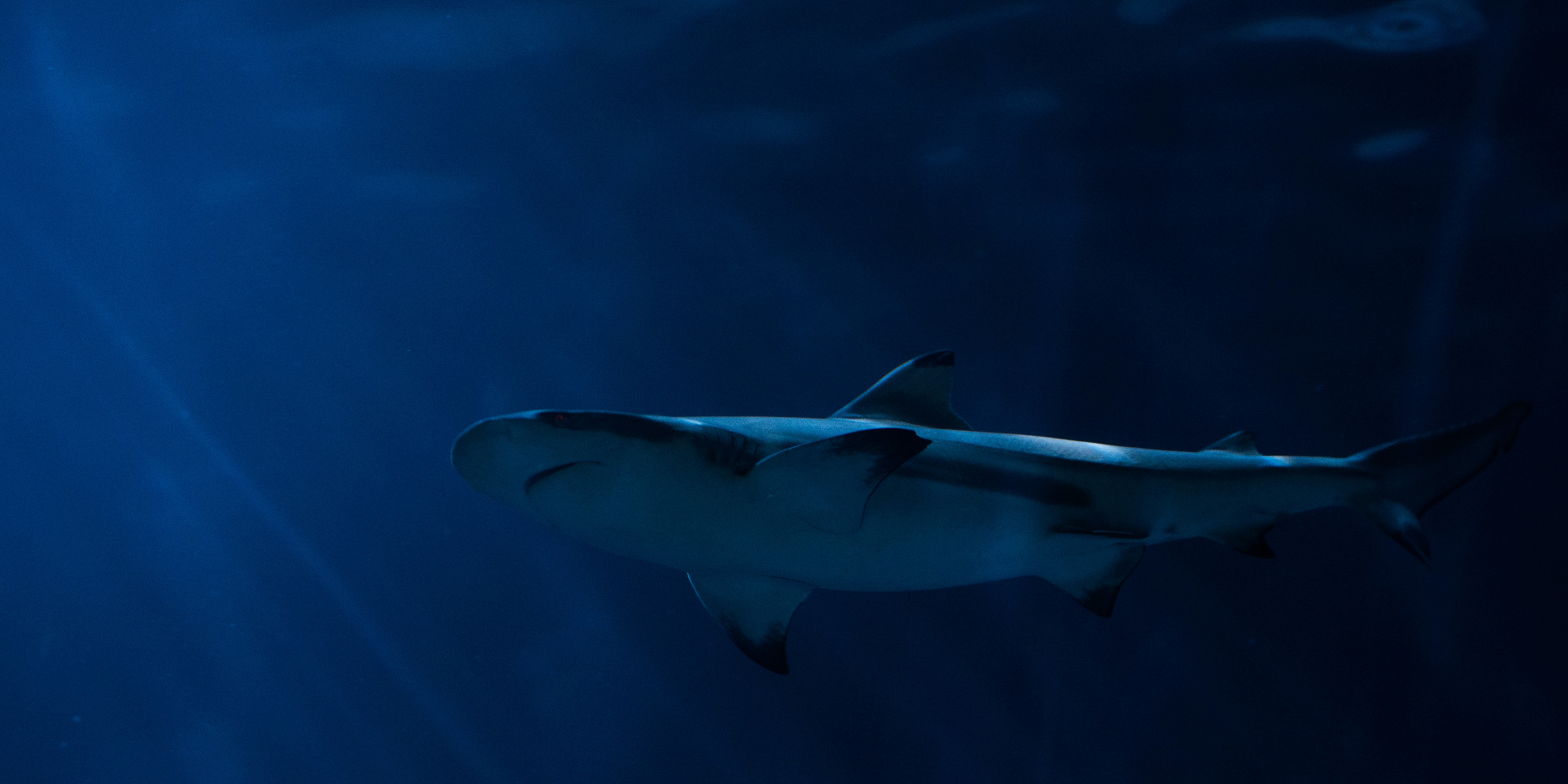

I waited four long years to see my first shark. I was diving in Komodo National Park in Indonesia at Castle Rock, a pinnacle where the coral reef clung to the rock against swirling currents.

Without warning, a blacktip reef shark surged past me, making light of the strong current that battered me backwards. Rather than fear, I felt awe. It had chosen to emerge from the blue.

I used to be scared of many things. Lightning, spiders, injections, and even the dark. I overcame each of these fears in turn, but there was always one remaining: sharks.

When I learned to scuba dive, I realised that the diving community does not see sharks in the same way as the media. Since they can be so elusive, it’s considered a privilege to spot sharks on a dive.

Original photo: Isabel Sommerfeld

On deck, we were educated by our Divemaster about the role of sharks in the reef, how vulnerable they are to fishing practices, and the common misconception that humans are on the menu.

There are many challenges facing shark conservation, not least their poor reputation.

The chance of being attacked and killed by a shark is one in 3,748,067, yet there is almost a primal fear of sharks that means even the mention of their name conjures up the word “attack”.

You cannot mention sharks without Spielberg’s Jaws resurfacing. The iconic movie poster of the great white shark lurking beneath an unsuspecting swimmer tapped into an innate fear that has since become ingrained in our culture. I bet you can even hear the ominous “dun-dunnn” of the cello.

It has implanted a seed of fear into our collective psyche. We know that we are vulnerable in open water as we are not as physically adept in that environment. This fear can manifest as irrational behaviour.

I was in the pool with my sister, testing who could hold their breath underwater for the longest.

Aged nine, I had just mastered letting a stream of bubbles escape the side of my mouth so I could sink to the bottom of the pool.

As I floated down, I focused on the shimmering patterns of light on the tiles until I reached them.

Without warning, my chest began to constrict. I felt a prickling in the crooks of my limbs. I snapped my head from side to side, expecting to see the unmistakable flash of fin.

My mouth opened in horror and a torrent of bubbles shot to the surface. To the bemusement of my sister, I struck out wildly until I reached the safety of the steps.

Despite knowing that it was impossible for a shark to be in the pool, I could not shake the feeling I was being hunted.

But Spielberg’s portrayal of a vengeful shark that targeted humans was a misconception of shark behaviour since sharks do not intentionally attack humans as prey, but often mistake them for seals or rival predators.

The movie, released in 1975, prompted a fishing frenzy, where thousands of fishermen hit the waters to catch trophy sharks. This took a big bite out of shark populations.

Biologist Dr Julia Baum estimates that between 1986 and 2000 great white populations dropped by 79% in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. However, other species of shark were affected too, with a 65% decline in tiger sharks and an 89% decrease in hammerhead sharks during the same period.

The movie was so damaging to shark conservation efforts that the writer, Peter Benchley, spent the rest of his life devoted to protecting the welfare of sharks.

Although Hollywood profits from the myth that sharks are the bloodthirsty sniffer dogs of the sea, in reality, you are 33 times more likely to be fatally attacked by a dog.

According to gorily fascinating statistics from the Florida Museum of Natural History, you are 11 times more likely to die from fireworks (a 1 in 340,733 chance), 761 times more likely to die in a bicycle accident (a 1 in 4,919 chance), and 60,000 times more likely to fall victim to the flu (a 1 in 63 chance).

A tracking website recently tallied the annual total of shark attacks on humans around the world at 98. The numbers of shark attacks have slowly increased year on year, but it has to be acknowledged that more people are entering the waters for fishing or recreation than ever before.

Despite such data, the fear persists, as if implanted.

“Do you have any concerns?” asked the surgeon, hovering above me.

The anaesthetic felt cold as it flooded my veins. “Are there any sharks in there?” I wondered aloud.

“Ten… nine… eight… seven…”

When I woke in the recovery room, the surgeon was beside me. “That wasn’t the first time a patient was worried about a shark in the operating theatre,” he told me with a wry smile.

While our fear of sharks continues to be propagated by the media, shark populations are plummeting at alarming rates, mainly due to the high demand for shark fins in Asia and unsustainable fishing in our seas.

For every fatal shark attack on a human, an estimated 25 million sharks are killed by humans per year. That means that the number of sharks currently estimated to be killed for their fins or meat is 100 million per year.

Despite China recently shunning shark fin imports, with an 80% reduction in shark fin soup consumption since 2011, there continues to be a growing demand for the “prestige dish”, which is often seen as a status symbol at wedding banquets.

In Singapore, the second-largest importer of shark fins, mounting pressures have caused a backlash against offering this delicacy on the menu. Yet the dish can still be found in many restaurants.

In spite of ethical concerns, there continues to be a demand for shark fins in Asia. This appetite has prompted China, Japan and South Korea to once again block attempts to ban the finning of sharks at the recent International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT).

Finning is the act of slicing the fins off a shark, then throwing the injured shark back into the sea. Many countries have banned this practice, but still allow the sharks to be killed as long as the carcass is brought back to land in order to accurately monitor numbers.

And so overfishing remains the biggest threat to shark species. Sharks have far more reason to be afraid of humans than the other way around, yet it seems we are reluctant to consider sharks as prey.

Original photo: Tchami

Shark conservation was late off the starting blocks, with serious attempts to protect shark species only being established in the late 1990s, with charities such as Shark Trust beginning their campaign to fight unsustainable fishing and the killing of vulnerable shark species.

However, the tide is turning as half of the world’s 400 shark species veer towards extinction. Great white sharks are threatened, along with other species such as hammerhead sharks, bull sharks, lemon sharks, and tiger sharks.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) cites that open water shark species are at risk of being caught by fisheries, or from the impact of overfishing. They state that 58% of these sharks are threatened with extinction, so the time for policy changes on fishing regulations is now.

Conservationists have worked hard to prove that sharks are worth more alive than dead, with a single reef shark being estimated to generate $73 per day in ecotourism ($200,000 over the course of its life), whereas its meat may only sell for $20 at market.

The ‘economic value of a shark has prompted some governments to enforce more fishing regulations in order to protect sharks and encourage ecotourism, which is more lucrative.

Original photo: Geoff Shuetrim

However, some practices such as cage diving or baiting sharks on diving expeditions are seen as irresponsible tourism since it is manipulating the behaviour of the animals for monetary gain.

Marine ecosystems need sharks to survive as they are a keystone species. Without them, there would be no coral reefs and our seas would become clogged with algae.

Scientists are unable to predict the exact effects of removing sharks completely since they have been in our seas for 450 million years. Nonetheless, sharks now face extinction as a result of human activity over the last two centuries.

The GVI Trust has partnered with Shark Guardian to promote better education about sharks, releasing a book called Sharks – Our Ocean Guardians to help conservation efforts in Thailand.

To find out more shark facts, get involved in a GVI marine conservation program or to participate in our lemon sharks project in Seychelles, please contact GVI.

From the postcard-perfect Coral Bay to the hidden beauty of Secret Cove, these spots promise stunning photos and unforgettable views.

GVI

Posted: August 29, 2024