From the postcard-perfect Coral Bay to the hidden beauty of Secret Cove, these spots promise stunning photos and unforgettable views.

GVI

Posted: August 29, 2024

Posted: August 23, 2019

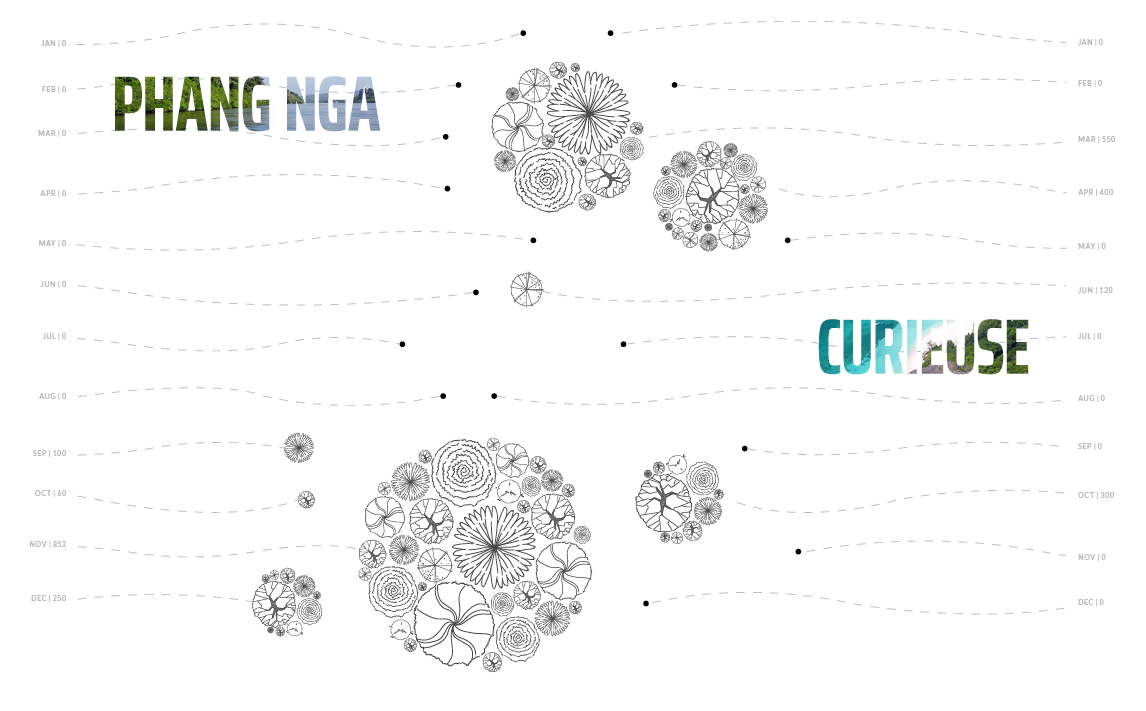

After a tsunami in 2004, there were concerns that the mangrove forest within the Curieuse Marine National Park (CMNP), Seychelles, was experiencing a decline in both size and number of species present. To assess these concerns, GVI partnered with the Seychelles National Park Authority (SNPA) and started monitoring the forest in 2013.

Seven species of mangrove are currently present in Seychelles, of which six were once present on Curieuse Island. Within the CMNP, you will now find only five species, along with a mangrove-associated species.

Mangrove ecosystems play an important role in ensuring a high level of water quality and clarity, and are essential for adjacent corals and seagrass to thrive by trapping sedimentation and land run-off. In addition, mangroves provide high-quality nutrients for both mangrove and sea-dwelling creatures, prevent coastal erosion, provide vital nurseries for a range of species (sharks, fish, crustaceans), and are important habitats for a variety of animals (birds, crustaceans, fish, and many more).

The mangrove forest on Curieuse is of particular interest. In 1910, a causeway wall was built across the bay in a failed endeavour by European settlers to rear sea turtles. This wall had a lasting impact on the bay. It reduced water intensity and provided a suitable environment for mangrove seedlings to settle and grow.

In 2004, a tsunami damaged the wall, allowing larger waves to enter the bay more frequently, and in turn, caused an influx of sediment. This altered the mangrove population structure by decreasing abundance and species richness.

I joined the mangrove monitoring program as a Science Officer after graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Marine Science and Ecology. I had previously worked with mangroves, including some species that are present on Curieuse Island, during my studies and loved exploring the sulphur-smelling, knee-deep muddy forests.

The current mangrove monitoring activities conducted by GVI staff and participants are part of a long-term project aimed at maintaining the ecological function of the mangrove habitat. In 2013, 28 permanent transects were placed in the mangroves and monthly data collection began.

Surveys were initially developed in an effort to determine the layout of the mangrove forest in relation to water patterns and salt concentrations. Mangroves are known to be difficult to rehabilitate and selecting the optimal site for planting each species is essential.

We ascertained that all species grow in a wide range of salinity from 0 to over 31 ppt (parts per thousand) and were found in water inundation levels ranging from 0 to 81+ cm. With the exception of the Xylocarpus species, which were found in much shallower water levels. Current surveys assess mangrove diversity and abundance, as well as looking at mortality and recruitment rates.

Original photo: “Mangrove roots in the Laguna de La Restinga” by Wilfredor is licenced under CC0 1.0

In 2015, five permanent quadrats were set up in various locations throughout the mangrove forest. Quadrats are square frames of a set size, in this case, 10m x 10m, placed in a habitat of interest and the species within these boundaries are identified and recorded. An additional three quadrats were installed within the forest in 2017.

From these biannual surveys, we have found that Rhizophora mucronata is the dominant species within the seaward edge of the mangrove forest, while no quadrats contained Xylocarpus species. R. mucronata and Bruguiera gymnorrhiza are the only species to have seedlings and/or saplings present within the quadrats.

Original photo: “mangrove roots” by Dennis Tang is licenced under CC BY-SA 2.0

While the current positioning of the quadrats allows us to collect consistent data on the mangroves in the seaward half of the forest, they exclude the middle and rear sections of the forest. As a result, species that distributed further inland are under-represented.

The majority of the seaward edge of the forest is also excluded, which is the area of highest concern as it is where we have observed the highest mortality rates. To undertake future assessments of mortality rates, and understand whether or not this phenomenon has penetrated further into the forest, it is vital that more permanent quadrats are set up along the seaward edge of the forest.

Since the partial destruction of the seawall in the 2004 tsunami, there have been concerns that the increased wave action and influx of sediment may be resulting in the degradation of the forest. If restorative planting of mangrove habitats is to go ahead, the removal of stress should be considered prior to attempting restoration.

There have been ongoing discussions about whether or not to rebuild the seawall. When considering the options, it is important to think of the implications that this may have, on not only the mangroves but also on the multitude of species that inhabit this area.

One option would be to not rebuild the sea wall. Allowing the mangrove forest to return to the state it was in before the wall was built in 1910. The concern surrounding this option is that it may lead to a decrease in its current high level of biodiversity.

Another alternative, that I would personally like to see in action, would be to create natural buffer zones using mangroves, enhanced seagrass beds, and coral reef restoration. This option reduces the amount of heavy construction conducted in the Marine National Park while also increasing the biodiversity of the area – a win-win.

Riley’s Encasement Method (REM) was developed to facilitate planting where shorelines have high-energy waves and in an effort to overcome the limitations of other mangrove planting schemes. Increasing the seagrass cover within the bay may assist in reducing the impacts of wave action and sediment influxes on the mangroves. Conducting coral reef restoration directly beyond the seawall could also assist in alleviating wave action on the mangrove forest.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation aims to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. One of the UN SDG targets is to protect and restore water-related ecosystems – mangrove forests fall within these ecosystems. Water services to society are provided by water-related ecosystems. Ensuring our mangrove forest is healthy is our way of supporting global efforts to improve water quality.

This is still a relatively new monitoring program and with continued data collection, overall trends will become apparent. With any luck, the data will suggest that the forest is able to achieve a high level of biodiversity on its own.

Original photo: “Soldier crabs marching through mangrove aerial roots” by Matthew Nitschke is licenced under CC BY 4.0

On the other hand, if the data suggests that a helping hand is required, I hope we can achieve restoring the mangrove forest to all its previous glory. The biggest challenge the mangrove forest faces is climate change. That is: sea levels rising, decreasing rainfall, loss of protection provided by nearby seagrass meadows and coral reefs.

An increase in extreme weather will negatively impact mangrove ecosystems and the services they provide. Maintaining, and restoring mangrove ecosystems will be difficult, yet crucial, moving forward.

This story comes from GVI’s Impact and Ethics report. To celebrate 20 years of work in sustainable development, we reflect on and showcase our impactful stories and data. Read the report in full.

From the postcard-perfect Coral Bay to the hidden beauty of Secret Cove, these spots promise stunning photos and unforgettable views.

GVI

Posted: August 29, 2024